Paulie McDermid: The Many Lorcas

March 1, 2015

Lorca makes the blood flow faster in my veins. A blood rush to the head and the heart.

This was my reaction when I found out that Aluna and Modern Times were going to produce Lorca’s perhaps most lyrical, visceral, captivating and stirring of tragedies, Blood Wedding.

Of course, part of me thinks they’re crazy to take it on. And I don’t think Bea, at least, would deny the charge. I mean, like so many works that have passed into canon, that get referenced as a touchstone of modern drama (European, at least), why tackle such a piece? Blood Wedding has been so widely read, widely translated, widely performed, studied, written about… Do you really want to risk it? There is risk involved. As with any “classic” text, so many feel ownership of it you can never have a piece of it for yourself. But even more so because it’s Lorca. As Paul Julian Smith has pointed out, Lorca’s one of those writers whose life and works seem inseparable, and, for those who see them as one and the same, their inseparability is an “article of faith”. Lorca is Blood Wedding, and Blood Wedding is Lorca. Blessed be.

You see, Lorca is more than a man, more than a writer, more than a poet, playwright, artist. Maria Delgado sums it up well when she writes about the mythology of Lorca: Lorca the icon, and the “cult” of Lorca, (which probably reached its zenith with his centenary in 1998 – after that year’s saturation of Lorcaness, Spain, at least, had reached peak Lorca). So many people know his works, know about his life, that Lorca is many things to many people. There are multiple Lorcas.

In his early days of renown, people even then conflated the author with his work. After the publication of his Gypsy Ballad Book, many who knew nothing more of him, except perhaps his Andalusian accent and dark complexion, imagined him a gitano (someone from the peoples who we now, more respectfully, refer to as Roma). There’s the bourgeois Lorca: his family was of a comfortable land-owning class. Granada’s a provincial little town, and Lorca, in an ultimately bourgeois way, had a love/loath relationship with it. Nowadays, Lorca’s works are safely assimilated into bourgeois theatre notions, in Spain and elsewhere.

Yet there’s also the socialist Lorca. Held up in many parts of the world, especially Latin America, for his vindication of social justice, for his defence of ordinary folk in the face of cruel totalitarian power, and his contempt for the ugly selfishness of the Right. Meanwhile, the progressive, though nostalgic, Left carries aloft on banners the republican Lorca as a face of martyrdom, assassinated by a Fascist militia at the very outbreak of Civil War hostilities.

Martyr too is Lorca to queer folk the world over. The queer Lorca is something of a patron saint to us sexual and gender dissidents. That’s really why they shot him, you know, as one of his murderers made clear: “two bullets in the ass for being queer”. In a time and place where misogyny and machismo were all encompassing, Lorca’s gender and sexual subversions really pissed them off.

And while some folk can’t get beyond Lorca’s Spanishness, there’s really no getting away from the many, many elements of his work that are seem universal in tenor, theme or concern. The great number of translations, versions and celebrations of his works found around the world give us an internationalist or intercultural Lorca. And of course, despite a sense of familiarity in his works, an intelligibility that open them up to many other cultures, sometimes the meaning of his verses and words seems so elusive, enigmatic or impenetrable that there is talk of a surrealist Lorca. It’s an easy tag that bundles him together with his friend, colleague and maybe lover (if you care), Salvador Dalí. But defining him as surrealist suggests a deliberate irrationality in his works and it ignores what Lorca said about his work having its own internal logic, what he called a “poetic logic”.

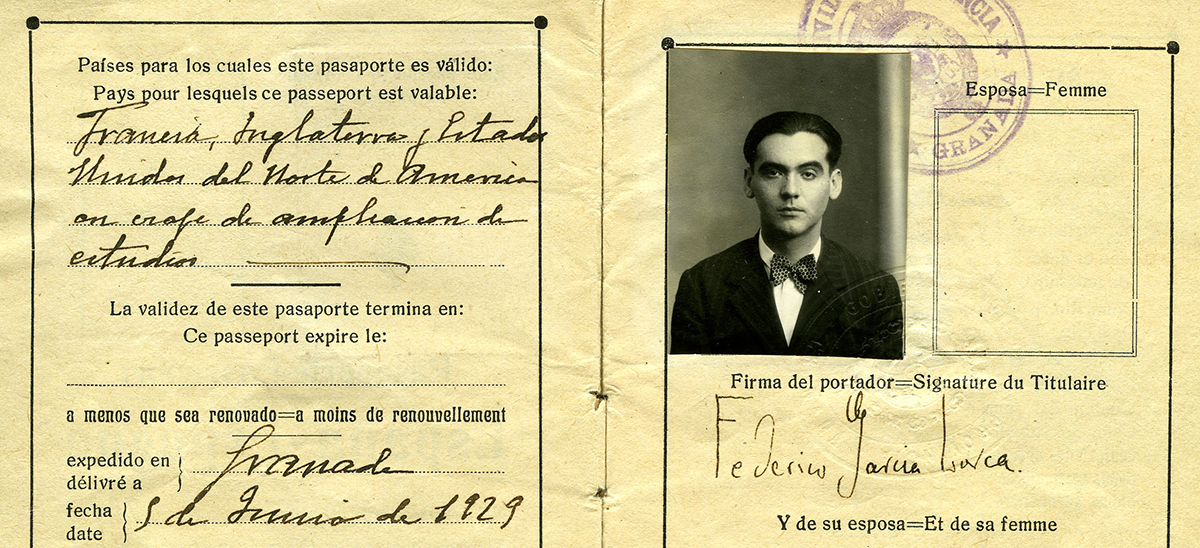

That’s only some of the Lorcas. They are the ones in public domain. So, you can guess that there are an equal amount of private Lorcas. Well, if you don’t mind, let me tell you a little about my own private Lorca. He is one I first met as an adolescent in a giant bookstore (remember bookstores?) in one of my home country’s major cities. Scanning the bookshelves lazily, drawn to a title or two, perusing, as you do, the cover of one book jumped out at me. It bore a photograph of a man in his late twenties, seated on a chaise lounge, wearing a quilted housecoat, I guess you would call it, and a cravat. His jet-black hair was swept and slicked back. I remember the posture: legs crossed and hands clasped in his lap, soft and timid. But I took in all that detail later. It was his eyes that drew me. Have you ever seen Lorca’s eyes? Sad they are, achingly vulnerable, and in some way softly defiant… like the shadow the Earth casts on the eclipsed moon to leave us with its waning crescent.

The picture, I later learned was a very personal, intimate Lorca in 1927, at his family home in Granada. And the book, which I bought of course, was a recently translated collection of his personal, intimate letters to friends and family. I couldn’t believe, as I read one letter after another, how playful and passionate, naughty and charming, pretentious and boastful, honest and energetic, seemed the man who wrote them. You’ll likely know the feeling: I felt, I imagined, I dreamt and I was certain, I knew him, I knew this man. And I liked him hugely, without hesitation. The years since his death, the distance of time, place, language and culture, I did not recognize. I saw only in the cover photograph and the letters inside, someone who was immediately familiar, someone I knew. I drank in his words and my blood became infected with Lorca.

I’d say now to Bea and Soheil: I know something about daring to take on Lorca. After much perambulation I came, as a graduate student in my late 20s, to embark upon some serious study of Lorca’s theatre. Not for the first time in my travels, I went to Spain. But this time, I went to Lorca’s hometown of Granada, where I lived for a while, teaching and reading, and in the end, writing perhaps the most robust chapter of my doctoral thesis. There I had many, many occasion to find myself faced with a Spaniard who asked, in that direct of Spanish ways, what can you, a ruddy, freckly, northern European, know about Lorca? You need to be Spanish to understand Lorca.

They have a point. I’ve learned to speak the language, to varying and wobbly command depending on how much I’m using it. And I know Lorca’s original texts much better than the translations. But I’m a guiri, a “babbling” foreigner. So how can I really understand Lorca? I think, but you’re more than welcome to argue with me, that that challenge to me – that my identity precludes me from knowing Lorca – goes back to the many Lorcas… My challengers know the Spanish Lorca, and they made him their own, with exclusivity. Yet, I insist I understand Lorca. I know him, I could say, because I know the queer Lorca. I could say: you have to be queer to understand Lorca. But let’s not go there. Let’s not fight over ownership of the public Lorca. I have my private Lorca, and still, it’s even simpler than that. What I understand are the forces that sweep through his verses and dramas, that run through the veins of works like Blood Wedding; they are the life forces of human mythmaking: love, desire, fate, destiny, family, betrayal, memory and grief. I too feel these forces. In my blood, I feel them. This is the Lorca I understand. This is the Lorca I know.

And now Aluna and Modern Times are staging this play for us here in Toronto! Do I need to say it? Come see! Come find your Lorca.

I was so lucky to have been included in early pre-production chats with Soheil and Bea about their Lorca, and why and how their Lorca. And in the first week of rehearsals, I was delighted to be allowed sit in with director and cast as they first started to really grapple with the script. With no official capacity in the rehearsal room, I was not so much some kind of textual advisor, as a bit of an awkward lump. Nonetheless, Soheil and the actors generously brought me into their conversations and listened patiently as I reflected on elements of the text and themes with them.

It was quite a luxury to spend so much rehearsal time just working through the text. Not all directors do this. Many actors feel it more useful to start putting bodily movement into the text, to embody what’s going on, rather than talk about it. But I think everyone agreed this was useful when working on Lorca. Especially in translation. The choice of Langston Hughes’ translation of Blood Wedding is a thoughtful one. I don’t know about you, but I heard and read some painful translations of Lorca. How do you render some of that verse and imagery? And not make English-speaking actors baulk? Well, it seems to me that if you want to translate stage dialogue full of verse and imagery written by a poet/playwright into something that makes sense, you might start with giving the text to a poet and playwright. Hughes was a contemporary of Lorca’s, a fan of his works, he spoke Spanish, and he was a popular and queer poet/playwright who drew on a sometimes stylized African-American idiom and cadence to compose his writings. There’s enough synergy going on with that to convince me.

What I had most to offer in the rehearsal readings were thoughts on how to engage with the lyricism of the play. I don’t think Lorca really bothered distinguishing much between theatre and poetry (or music for that matter), and for many folks who work with, who really work with, his text, it can be a challenge to fold yourself into his words and images. And yet, the actors must do this – fold themselves into his lyrical universe. Each theatre artist has their own way of doing that. Let me not try to spell out that process for you here. Each actor can better articulate the process. Instead, I can tell you that what I saw in my brief visits to the rehearsal space was a joy. I was so taken with the excitement, energy and determination that the actors were bringing to the task. My blood flowed faster listening to their reflections on the text, hearing their insights, listening while they were figuring out what each word, each verse, each speech could mean for their character, their character’s relationships, their character’s destiny in the drama. It was a joy to read the text again through the smart and compassionate eyes of this director and these actors.

I bowed out of the rehearsal process realizing they were each already well on their way to finding, from among the many Lorcas, their own personal, private Lorca. I could feel it in them. More blood flowing faster, something quickening within, an infection they may never be cured of.

This post was written by Dr. Paulie McDermid, a member of Aluna Theatre’s Board of Directors, as well as a queer performance artist (possibly better known to you as the host of Aluna’s Cabaret, Ms. Philomena Flynn-Flawn), and an academic specializing in the theatre works of Federico García Lorca.

Paulie will join Soheil Parsa and Ramin Jahanbegloo for a post-show panel discussion, ‘The Other Lorcas’ after the Sunday March 15th performance of Blood Wedding | Bodas de Sangre at Buddies at Bad Times Theatre.

Visit Buddies in Bad Times for show information and tickets.