Yuyachkani, Antigona, and memory in Peru – by Brian Batchelor

February 18, 2014

no podemos encontrar reconciliacion si no conocemos la verdad.

(Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación)

A present without memory condemns us to a poor future. To believe that today owes nothing to yesterday allows us to think that we have no responsibility to tomorrow. On the contrary, memory and the imagination compliment each other since they allow us to represent what has already passed and what one day might occur.

(Miguel Rubio quoted. In A’ness 395)

This post deals with Grupo Cultural Yuyachkani’s production of Antígona and its connections to the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission. I had the pleasure of seeing Antígona this past summer when it was performed at the Centro Hemisferico in San Cristobal de las Casas. It is a powerful performance that explores how we sort out/confront the trauma of violent events. A photograph of an indigenous woman in mourning garb running across an empty public square inspired performer and Yuyachkani member Teresa Ralli to create this production (A’ness 405). The photo reminded Ralli of Antigone, hurrying across an empty battlefield in order to give her dead, exiled brother a proper burial. Yuyachkani viewed Peru’s many survivors – relatives of the disappeared and victims of state violence – as the country’s own many Antigones (A’ness 405).

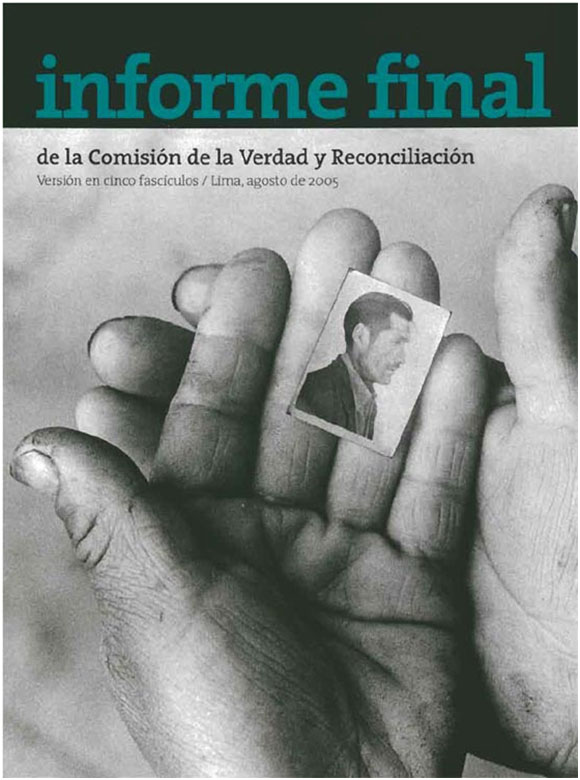

On August 28, 2003, the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación) released its final report chronicling the violent, two-decade internal conflict that saw up to 70 000 Peruvians killed. The history of Peru’s internal strife is complex but here follows a general outline of this conflict (I used the following websites as sources for piecing together this history: Peru Support Group, Centre for Justice and Accountability, and the New York Times). It was sparked in 1980, when Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso), a Marxist/leftist political group, refused to take part in the national elections and instead launched a low-intensity guerilla war against the State. In 1982 Shining Path intensified this conflict by forming an official armed force known as The People’s Guerilla Army. 1982 also saw the formation of another leftist military and political group, the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA). However, the primary sides involved in Peru’s internal conflict were governmental forces and Shining Path; MRTA played a relatively minor role. This conflict affected the entire country, but fighting – fueled by guerrilla warfare and counter-insurgency tactics – was generally concentrated in the mountainous Ayacucho region in south-central Peru, a region largely populated by poor campesinos (primarily indigenous rural peasants and farmers).

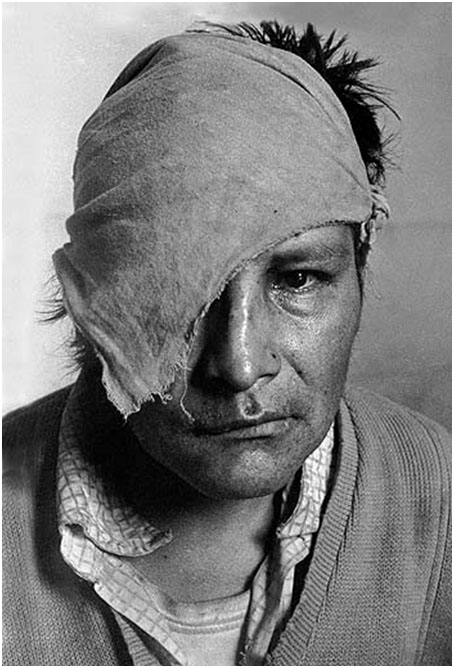

In 1983 the government declared a state of emergency throughout the Ayacucho region, allowing the military commands to become the highest political and judicial state authority in these zones. These authorities quickly applied a repressive campaign targeting campesinos, whom the government assumed supported Shining Path. This saw government forces commit a series of extrajudicial executions, forced disappearances, torture, and sexual violence against women; Shining Path members committed similar atrocities against those thought to have nationalist sympathies. The administration of Alberto Fujimori, who took office in 1990, changed this sweeping counterinsurgency strategy to a more targeted, counter-subversive one. This shift decreased the number of generalized human rights violations but increased the number of deliberate and planned violations, often in the form of forced disappearances. Shining Path also employed extreme violence in order to intimidate or control a population in its area of operation. In 1992 Fujimori dissolved congress, suspended the constitution and purged the judicial system, effectively creating an authoritarian regime. Anti-terrorism laws enacted by the state ignored due process and legal defense, extended periods of police/military detention and encouraged torture as a means to gather information. Thousands of innocent civilians were caught up in anti-terrorist witch-trials, the result of juridical arbitrariness. Fujimori’s rule further eroded the rule of law by enacting amnesty laws and granting impunity for the members of government death squads.

Shining Path’s leader, Abimáel Guzmán Reynoso, was also captured in 1992, which led to a reduction in political and state-sponsored violence and extra-juridical executions. Tensions slowly lessened over the next couple of years and, in 1999, Shining Path was splintered upon the arrest of its new commander. In 2000, Fujimori made an unconstitutional bid for a third term at presidency; he shortly thereafter resigned – and was simultaneously booted from office – in the midst of bribery and corruption scandals, and fled to Japan. Peru then worked towards restoring democracy and overseeing new free and fair elections. Peru established its Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2001.

We can look at Truth and Reconciliation as operating in both official/political as well as symbolic ways. Henry Steiner reminds us that the term “Truth and Reconciliation Commission” is an umbrella phrase used to designate a governmental organization that “takes many institutional forms, serves diverse functions, includes various memberships, and enjoys a range of powers and methods” (3). That is, these commissions are different structures and processes that change accordingly from country to country. Despite their many different forms, they tend to hold similar functions: their powers and methods are often centered at registering, documenting or otherwise making official gross violations of human rights, enactments of state-sanctioned violence, and abuses of power committed by a former regime or authority (Steiner 3). Truth and Reconciliation, as process, becomes a tool that nations use to deal with their traumatic past while also publically communicating or signaling their need to break from this past. However, truth and reconciliation also works to symbolically bring about – to reconcile – justice, or Truth, within a nation’s history, by representing incidents and periods of injustice. Shoshanna Felman, commenting on and using Walter Benjamin’s term, calls this process Judgment Day: “the (revolutionary, legal) day that will put history itself on trial, the day in which history will have to take stock of its own flagrant injustices” (15). Truth and reconciliation becomes a process of recognizing unlawful, extrajudicial abuses and violations of law, but also of acknowledging and pledging to depart from the systemic and social order that enabled, allowed and ignored such abuses.

Peru’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission report outlined the massacres, forced disappearances, acts of violence against women, human rights violations, and extrajudicial and lawless abuses by the justice system, but also called out the systemic racism and classism that had permitted such abuses to happen. Importantly, the Commission noted that: more than 40 percent of the deaths and disappearances reported to the TRC were concentrated in the Ayacucho Region; that 79 percent of the total victims reported across Peru were of the campesina population; and that 75 percent of the victims who died during this internal conflict spoke Quechua or another native language (source). This last figure is particularly shocking given that the same group counted for only 16 percent of Peru’s total population according to its 1993 census. The Commission also noted that Peru’s military forces came primarily from urban areas and did not speak indigenous languages. Therefore, the Commission laid bare the fact that racial and cultural discrimination towards a poor, rural, indigenous population played a fundamental role in causing and perpetuating this conflict.

![Memorial stones with the names of the dead to be placed at the El Ojo que Llora [The Eye that Cries] monument in Lima Peru. Photo by Pilar Oliveres](https://www.alunatheatre.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/by-pilar-oliveres.jpg)

When the Truth and Reconciliation Commission gathered in multiple towns in the Ayacucho Region in 2002, with the task of hearing testimonies of survivors and witnesses, Grupo Cultural Yuyachkani was also present. Yuyachkani had been asked by the commission to perform outreach works in communities where public hearings were to be convened (source). To accomplish this, Yuyachkani developed two kinds of performance. First, it staged informative pieces that would educate people on the hearings’ intentions and encourage them to attend. Second, it developed more imaginative acts that would symbolize both a break with past violence and the country’s move towards a more peaceful, stable future (A’ness 399). Accordingly, Yuyachkani’s performances were engaged with facilitating the expression of trauma as well as enacting the transition or break from this (traumatic) past. These performances also connect to performances evoked by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission: the performance of expressing trauma or of bearing witness by survivors. Here testimony, like performance, serves as a means of “re-membering and transmitting social memory” (Taylor). Yuyachkani’s performances spoke to the commission’s desire to gather truths through memory and re-membrance in order to produce social change. According to Diana Taylor, Yuyachkani’s works “create a critical distance for claiming experience and enabling, as opposed to collapsing, witnessing” (Taylor).

Yuyachkani’s Antígona takes seriously this idea of witnessing, social memory and performance as a means to both remember and deal with a traumatic past in hopes of a better future. The play was developed in 2000, prior to the start of Peru’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. As part of the developmental process, Yuyachkani invited wives, mothers, sisters and daughters of Peru’s disappeared to share their stories (A’ness 405). These survivors told stories of “inadequate responses and failed attempts in the face of military might” to find their missing relatives (Taylor 207). These testimonies have been worked into the play: not only have they inspired playwright Jose Watanabe’s script, but the gestures, pauses and tones of those bearing witness have been worked into the characters by the play’s single actor, Teresa Ralli. According to Shoshana Felman, “life for the dead resides in a remembrance (by the living) of their story; justice for the dead resides in a remembrance (by the living) of the injustice and the outrage done to them” (15). Antigona forces us to deal with the injustices committed and trauma caused during Peru’s internal conflict. It remembers the victims’ stories and it expresses the outrage done to them; and it allows us to bear witness.

Unlinked Works Cited:

A’ness, Francine. “Resisting Amnesia: Yuyachkani, Performance, and the Postwar Reconstruction of Peru.” Theatre Journal 56.3 (2004): 395-414. Print.

Felman, Shoshana. The Juridical Unconscious: Trials and Traumas in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard U P, 2002. Print.

Felman, Shoshana and Dori Laub. Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History. New York: Routledge, 1992. Print

Steiner, Henry J. Truth Commissions: A Comparative Assessment. Cambridge: World Peace Foundation, 1997. Print.

Taylor, Diana. The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. Durham: Duke University Press, 2003. Print.

See Antigona Feb. 27 + 28 2014 at #RUTAS2014

Attend a theatre creation workshop by Miguel Rubio